1. Probabilistic ML: What is it? Why use it?#

Congratulations!

You’ve been hired to join the machine learning team at the Intergalactic Hypothetical Hospital (IHH), where you’ll be leveraging routinely collected medical data to help improve treatment for beings across the galaxy.

1.1. Your Role at the Intergalactic Hypothetical Hospital (IHH)#

About. The IHH is a research and teaching hospital located in the far corner of the universe. It serves a large number of intergalactic beings in the area. Like many modern hospitals, it collects large amounts of data about its patients (with their consent, of course), with the goal of leveraging this data to improve patient care. Unfortunately, doctors are incredibly busy focusing on the patients; when a new patient arrives, they don’t have time to inform their care based on the data they have. That is, they don’t have time to comb through all previously collected data, find similar patients, and determine how care for previous patients informs care for new patients. Moreover, they don’t have time to look at population-level trends or use data to research new treatment methods.

The Machine Learning (ML) Team. As a result, the IHH has created a new ML team—the first of its kind! And they have hired you to join them. The goal of the team is to assist IHH researchers and clinicians in:

Answering scientific questions, like better understanding the course of certain diseases.

Develop predictive models to identify patients at risk of certain diseases.

The challenges they encounter in their data are unique, so as a result, you may have to develop new ML methods to address their unique problems.

What is ML? Broadly speaking, ML is a paradigm of Artificial Intelligence (AI) that allows a computer to learn patterns from examples. In contrast, traditionally AI focused more on algorithmic/case-based reasoning. Now, the two terms are used more interchangeably. Nonetheless, let’s illustrate the difference.

AI via algorithmic/case-based reasoning. This paradigm is typically applied to problems where we have a good understanding of the mechanics. For example, suppose you wanted to play a game of tic-tac-toe against your computer. You can enumerate all possible courses of the game. You can program the computer to look at all possible future courses, and only choose ones in which it will win/tie.

AI via extracting patterns from examples (i.e., ML). This paradigm is typically applied to problems in which we don’t have as good of an understanding—problems for which we cannot write down if-else rules, telling the computer what to do. In these cases, it’s easier to provide the computer with examples—inputs and outputs—and have the computer “figure out” how to map the inputs to the outputs. As in the case of the IHH, imagine you are testing the effect of a new medication. You want to predict a patient’s blood pressure as a function of the medication’s dose. It would be hard for you to write down precise rules (e.g. if dose is \(x\), then blood pressure is \(y\)), since the biology underlying the medication is complicated, and influenced by each patient’s specific physiology (i.e. each patient reacts differently to the medication).

Your Role. Your role at the IHH requires you to consider three aspects of ML method application and development:

Safety. Patient safety is everything. As such, the ML methods you develop must be accurate; an incorrect prediction may cause patients harm. Moreover, in cases where it’s not possible to make accurate predictions, your ML methods must indicate to its users the limits of their knowledge (i.e. they must quantify uncertainty). For example, if a patient arrives at the IHH whose profile is different than all previous patients your ML method has seen, it should flag it for careful clinician screening.

Validity. The models you develop must be scientifically plausible; otherwise, IHH clinicians won’t be able to use them to advance clinical science.

Ethics. Whenever computerized systems interact with humans, we have to proactively think of ethical challenges we will face; for example, what if our ML methods are less accurate for one group of patients? When things go wrong, who is held responsible?

How can we address these challenges? You will use a specific paradigm of ML—the probabilistic perspective. This perspective provides us with tools to begin thinking about these questions.

Diversity of backgrounds, identities, and lived experiences. But as you will see, this paradigm won’t be enough. On its own, it will not give us safe, valid, and ethical ML systems to use. Model development and application requires us to consider not just the technical components, but also the social components surrounding the technology. We call the overall system a sociotechnical system:

Developing safe, valid, and ethical ML systems is a multi-faceted, open challenge—one that requires a diversity of perspectives. Luckily, the IHH’s hiring practice values a diversity of backgrounds, identities, and lived experiences. This is our biggest asset.

1.2. What is Probabilistic ML?#

In a loose sense, there are two main paradigms to ML. There’s what we’ll call here the optimization perspective and the probabilistic perspective. These two perspectives aren’t mutually exclusive—there are ML methods that can be described by both—but there are also methods that uniquely belong to each. Even more importantly, each accompanies a specific way of thinking.

The Optimization Perspective. In the optimization perspective, we formalize our goal into a loss or objective function. For example, suppose we’re given a data set, \((x_1, y_1), (x_2, y_2), \dots, (x_N, y_N)\), in which \(x\) is the dose of medication and \(y\) is the resulting blood pressure. Our goal is to learn to predict the \(y\)’s from the \(x\)’s. That is, we want to learn a function \(f\) that, given a value of \(x\) will return \(y\). We can encode our goal into the following loss function:

This function computes the average error between the predictions, \(f(x_n)\), and the data \(y_n\). Then by finding a predictor \(f\) that minimizes our loss, we find a predictor that makes accurate predictions on our data. We then hope that our \(f\) will continue to make accurate predictions for future data points. The name of the game behind the optimization perspective is coming up with a loss function that encodes your goals.

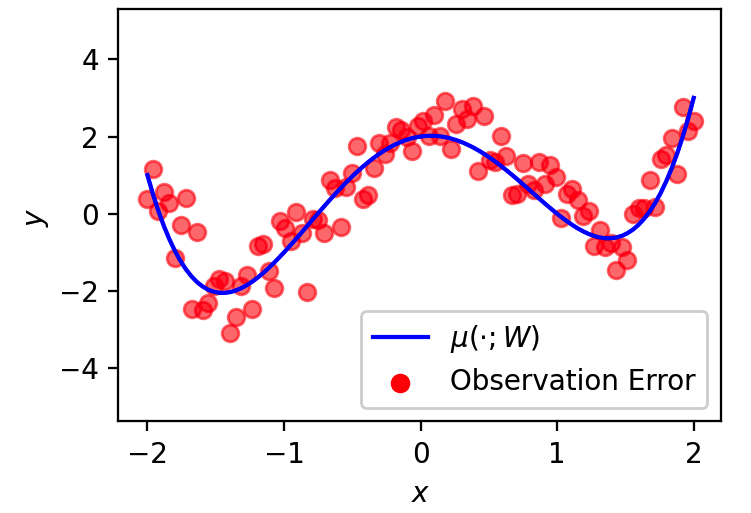

The Probabilistic Perspective. In the probabilistic perspective, we take a different approach. Instead of directly writing down a loss function that encodes our goal, we formalize our beliefs about the data into a “story” of how the data was generated. As an example, consider the model that predicts blood pressure given a dose of medication. For this model, our story can be something like:

Measure the dose, \(x\), and give it to the patient.

Due to the medicine, the patient’s true blood pressure is now \(\mu(x)\). Notice that \(\mu(x)\) is a function of \(x\), since it depends on the dose.

We measure the patient’s blood pressure. Since the device’s sensors aren’t perfect, we assume the measured blood pressure, \(y\), is near the true blood pressure, \(\mu(x)\). Specifically, we assume it’s \(\pm \sigma\) around \(\mu(x)\), with a higher probability of being closer to \(\mu(x)\).

Fig. 1.1 A visual illustration of the generative story.#

This story describes how the data is generated. If we were to write it with more mathematical specificity, as we will learn to do in this course, this story is a probabilistic model.

Notice that there are a few missing pieces in the story. First, we didn’t say what \(\mu\) is—just that it’s a function. Second, we didn’t say what \(\sigma\) is. Using algorithms from statistics, we will fit the model to data and estimate these missing pieces. Some of these algorithms will end up minimizing some loss function (like in the optimization perspective), and some will not. Even if we end up with a loss function, the process that led us to this objective function will have a very specific flavor and philosophical underpinning—it will always be concerned with probability distributions in some way.

Next, let’s highlight some of the advantages of the paradigm.

1.3. Why Use Probabilistic ML?#

Advantage 1: Distributions \(\rightarrow\) Uncertainty Quantification and Generative Models. In safety-critical applications of ML, uncertainty matters just as much as accuracy. The probabilistic perspective will allow us to capture the uncertainty of our method’s predictions (they will tell us when they are unsure about a prediction). What is uncertainty exactly? and how will we quantify it? Stick around to find out.

Next, the probabilistic perspective will allow us to develop generative models; for example, models that can convert text into high-resolution images, generate new musical compositions, etc. These models are probabilistic because they learn the distribution of the data they are given.

Fig. 1.2 Example of a Generative AI that generates a photo-realistic image from a sketch, taken from this website.#

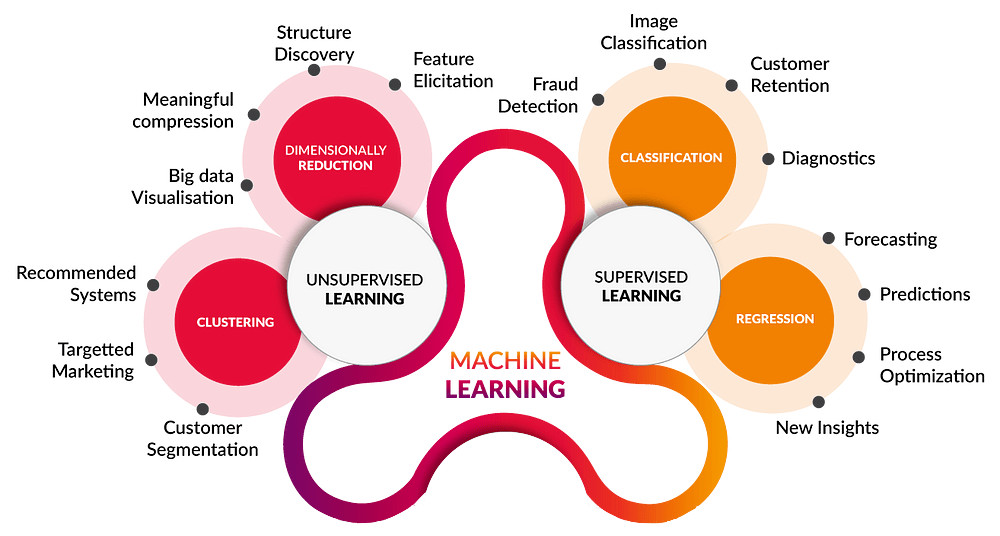

Advantage 2: Unified Framework \(\rightarrow\) Create/Analyze New ML Methods. You may have heard of different “types” of ML algorithms, like supervised ML and unsupervised ML (no worries if you haven’t—the details aren’t important):

Fig. 1.3 Types of ML methods, adapted from this website.#

Supervised ML typically refers to predictive methods—methods that predict a “label” \(y\) from an input \(x\) (as we did in our blood pressure example). The label “supervises” the method to give us the desired output. In contrast, unsupervised ML are only given inputs \(x\) and are asked to predict some label with useful properties. In this sense, they are “unsupervised.” For example, given a collection of patients’ medical histories as inputs, \(x\), we may want to cluster similar patients. We can then see if groups of similar patients benefit from similar treatments, etc.

This taxonomy of ML methods largely comes from the non-probabilistic perspective, since under this perspective, each method requires a different derivation, different fitting algorithms, and different theoretical analyses to understand its properties. This poses two challenges for developing new ML methods:

It’s hard to come up with a brand new ML method if we don’t have a unified framework for developing methods.

Every method you develop will need a brand new implementation, analysis, and justification—that’s a lot of work!

In contrast, the probabilistic perspective allows us to derive all of these methods under a unified framework. This framework will allow us to develop unique methods more easily—e.g. methods that have supervised and unsupervised components—and to better analyze these methods. We will therefore abandon this taxonomy in the class.

Advantage 3: Explicit Modeling Assumptions \(\rightarrow\) Highlights Subjectivity. While we’d like to think of ML systems as data-driven wizardry—you just give it data and it does the “right thing”—we’ll show in this course that this is a myth. It’s not theoretically possible to build such a system; all systems make assumptions. For safety-critical applications, like the ones at the IHH, it’s important that these assumptions are explicit. This is another strength of the probabilistic paradigm. In expressing our beliefs about the data via generative story, we list all assumptions we’ve made about the data. This will allow us to better interrogate our assumptions when our method behaves poorly (e.g. when our method is inaccurate, unfair, over-confident, etc.).

1.4. Course Structure#

This course consists of several parts, outlined below. We designed the course to cover the probabilistic model paradigm quickly (parts 1-3), so we can instantiate it in a variety of ways to derive popular ML methods (parts 4-5). The idea behind this design is that it highlights how all ML methods can be unified under the same paradigm. In each part of the course, we will always:

Center concrete tasks from the IHH. This is because it’s not possible to responsibly and ethically evaluate an ML model without considering the context in which it will be used.

Center ethics. As we hinted before, the course will highlight how ML systems are inherently subjective, and informed by implicit societal values and norms. Because of this, we must question the ethics implied in our goals, methods, evaluation procedures, etc.

Part 1: Introduction. Before starting to learn ML, we’ll get comfortable with Jax, a popular Python library for high-performance numerical computing. This library powers many ML libraries and is popular amongst ML researchers. We will use it as the basis for all code we write in the course.

Part 2: Directed Graphical Models. We’ll then shift over to learning the language of probabilistic models. That is, we’ll learn how to specify probabilistic models (like the generative story above), using probability distributions. We will start to gain intuition for what types of models are useful for which tasks. Will do all of this in NumPyro, a probabilistic programming language. NumPyro will allow us to translate our generative story directly into code we can run.

Part 3: Frequentist Learning. Using the language we developed in the previous part, we will now introduce our first model-fitting algorithm. With the language to express models and an algorithm to fit models to data, we will next begin to explore different types of commonly used ML models: predictive and generative models.

Part 4: Predictive Models. The first model class we’ll explore is predictive models. As the name suggests, these models are designed to make predictions (like in the dose / blood pressure example), and represent “supervised learning.” We will also learn how make our models expressive using tools from Deep Learning (specifically, neural networks).

Part 5: Generative Models. The second model class we’ll explore is generative models. As the name suggests, these models can generate realistic-looking synthetic data (like those text-to-image models you may have played with).

Part 6: Bayesian Inference. Now that we’ve instantiated the probabilistic ML paradigm a number of times, we’ll introduce a second model-fitting algorithm. This model-fitting algorithm will allow us to quantify uncertainty.

Part 7: Special Topics. Finally, we will connect the topics covered in class to current probabilistic ML research.

1.5. Deconstructing the Culture of AI#

We, as a society, hold beliefs about science that may be romanticized and inaccurate. These ideas can be exclusionary in the way we define a typical scientist and how science is done. These notions about science can also become obstacles for us as a community to perform rigorous, inclusive, and useful science, impede us individually in our professional growth, by contributing to unrealistic self-expectations (and therefore poor mental health), and hinder our ability to build supportive academic communities. What are these misconceptions? How can we address them?

Exercise: Societal Misconceptions about AI

Part 1: Watch this video of Iron Man developing and debugging a new suit. What societal misconceptions about CS/engineering/AI does this video endorse? Think both about who does computer science, as well as about what’s the day-to-day experience of doing CS.

Part 2: Below is a collection of common, reasonable, and expected experiences in CS/AI/ML classes—you may find yourselves relating to these (the course staff certainly did!). In addition to representing a common, valid experience, each statement is further endorsed by common societal misconceptions. Can you identify the misconceptions behind each statement?

I’m worried this class will be too difficult in terms of math.

I’m worried this class will be too difficult in terms of coding.

I’m worried I don’t have the right background for the class.

I’m worried that my background/skill set will not be valued by my peers.

I’m worried I won’t do well in the class.

Part 3: Individually and as a community, how can we address these common challenges?

Acknowledgements. This section is adapted from Yaniv Yacoby’s offering of CS290 at Harvard.